US Foreign Aid Planning Tool Drafts Put America First, Health Impact Last

It's okay dude. I'm not mad at you.

This post is dedicated to Renee Nicole Good who was shot and killed by ICE in Minnesota this week, seconds after she uttered the words in this post’s subtitle and closing line to her assassin. For Renee and all the people, mainly Black and brown, who have been, and are yet to be, slain even after they’ve smiled and tried to deescalate and disengage. For Renee and all the people, mainly Black and brown, who show up in situations capably holding rage at the system and nonviolent intentions toward individuals representing the state and get killed anyway. For Renee and all the people, mainly Black and brown, who drive safely and get killed anyway. And for all those people who will keep on showing up, standing strong and rejecting institutions that breed hate and endorse murder even though this killing makes them even more afraid. May her memory be a blessing and a bright light on the way to the world she, her family and all humans deserve.

The series of planning tools and explanatory documents to be rolled out in the coming weeks for countries receiving funding under the America First Global Health Strategy prioritize US interests and pay scant attention to strategies for saving lives and preserving health impact. Submitted for approval late last week, the versions of the tools and documents that I have reviewed reinforce the new reality of American foreign aid for health:

Extraction and transaction have replaced destruction and disengagement.

Replacement isn’t elimination. Extraction can beget destruction: witness our planet’s ravaged forests, boiling oceans and poisoned rivers. Whether these agreements plunder, pillage and scorch, or preserve, strengthen and sustain is entirely up to African civil society, impacted communities, service providers and government officials. To these individuals: I am convinced that the fate of the humans whose health and lives depend on how this money is spent is entirely in your hands.

Let’s start with a wee recap of where things left off back in 2025, and what transpired during the weeks when this Stack went silent for the long dark night of the solstice, and the two weeks that followed.

Fourteen MoUs guided by the America First Global Health Strategy have been signed with African countries that used to receive substantial US foreign aid for HIV/AIDS, maternal child health, immunizations and other non-health humanitarian programs essential for health societies. Just three of these MoUS (Liberia, Kenya and Uganda) are circulating in public, and only one of those (Kenya) was officially released, along with the Data and Specimen Sharing Agreements.

There is no sign of the by-disease-area table that was developed, I am told, for every MoU, nor is there any evidence that the transactional agreements for mining rights, mineral concessions and military presence in fragile conflict zones are captured in any annex—even though it is highly plausible that the health-related funding will be pulled from any country that fails to meet these off-book agreements, and sustained in the face of mediocrity and failure in health outcomes.

In short, at the end of 2025, billions of US dollars had been committed to sovereign nations for health aid with information about the nature of the agreements limited to slender, self-congratulatory press releases that offered blind items (I see you Starlink—and I know you see me!1) and reinforced, with admirable message discipline, that this Department of State cares about the number of agreements its signed and not the number of lives saved.2

During the wind-sprint to complete the MoUs, the message started circulating3 that the Implementation Planning period would be when the details got hammered out. This period is supposed to start on the date of signing and end on March 31 2026.4 This period is supposed to be when the details get hammered out. When the message that speed was needed started circulating, it came paired with the rationale that it was important to move fast and get agreements so that the parties could get down to the nitty gritty of figuring out who would do what, where and for whom in order to save lives.

That’s what was said. (Whew, that’s the end of that passive voice bonanza).

That’s not what’s coming. The documents I’ve reviewed make it clear that a detailed strategy is far from guaranteed by completing them.

Indeed, a strategy will only possible if the plans are made by an inclusive, multistakeholder coalition of African stakeholders—including civil society, impacted communities, faith leaders, non-governmental service providers, private sector and government partners—who refuse the tyranny of America’s low expectations.

In the text that follows, I explain this line of thinking. All of my assessments are based on documents that are sensitive but unclassified and are, to my knowledge, close or identical to those submitted for approval. They may be changed before release. This caveat applies to all the following content.

I will be posting more on this in the coming days. In this post, the topics I cover are:

The Implementation Agreement direction on strategy narratives

The Implementation Agreement direction on pre-requisites for the purchase of non-US manufactured commodities

The Implementation Process Overview + available MoUs + Implementation Agreement Template on which entities are likely to receive funds on April 1 2026

The Implementation Agreement direction on strategy narratives

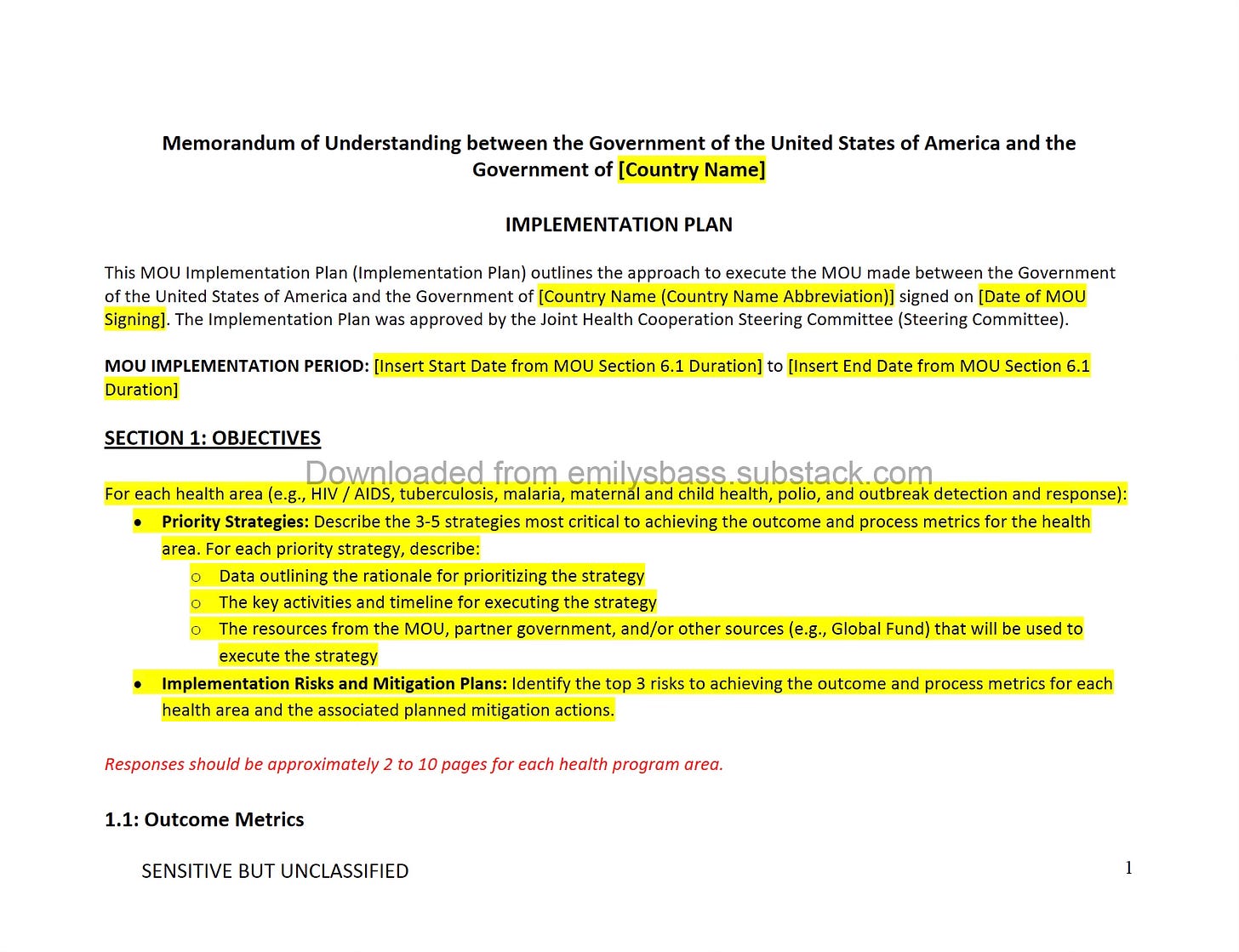

The Implementation Plan Template section on strategy - reproduced in the orange block below and in a reformatted version of the source document in the screenshot, and finally in the full pdf document at the end, states:

For each health area (e.g., HIV / AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, maternal and child health, polio, and outbreak detection and response): Describe the 3-5 strategies most critical to achieving the outcome and process metrics for the health area. For each priority strategy, describe:

o Data outlining the rationale for prioritizing the strategy

o The key activities and timeline for executing the strategy

o The resources from the MOU, partner government, and/or other sources (e.g., Global Fund) that will be used to execute the strategy

Implementation Risks and Mitigation Plans: Identify the top 3 risks to achieving the outcome and process metrics for each health area and the associated planned mitigation actions.

Responses should be approximately 2 to 10 pages per program area.

Alt text: A screenshot of a pdf document that I reformatted into Calibri (serifs are my jam, but so is disability justice.) I reproduced the same text above this image which has yellow highlighting in some places and red text stipulating the page length and a watermark that this came from my Substack which will always be free, never paywalled, and which sometimes gets to things before other sources. If you have the means to support as a paid subscriber and/or if you know that three or more of your staff are free subscribers, (1) good on you for making payroll and (2) please make a financial contribution to keep it free for folks who can’t. There is a group subscription discount available here: https://emilysbass.substack.com/c6545e38

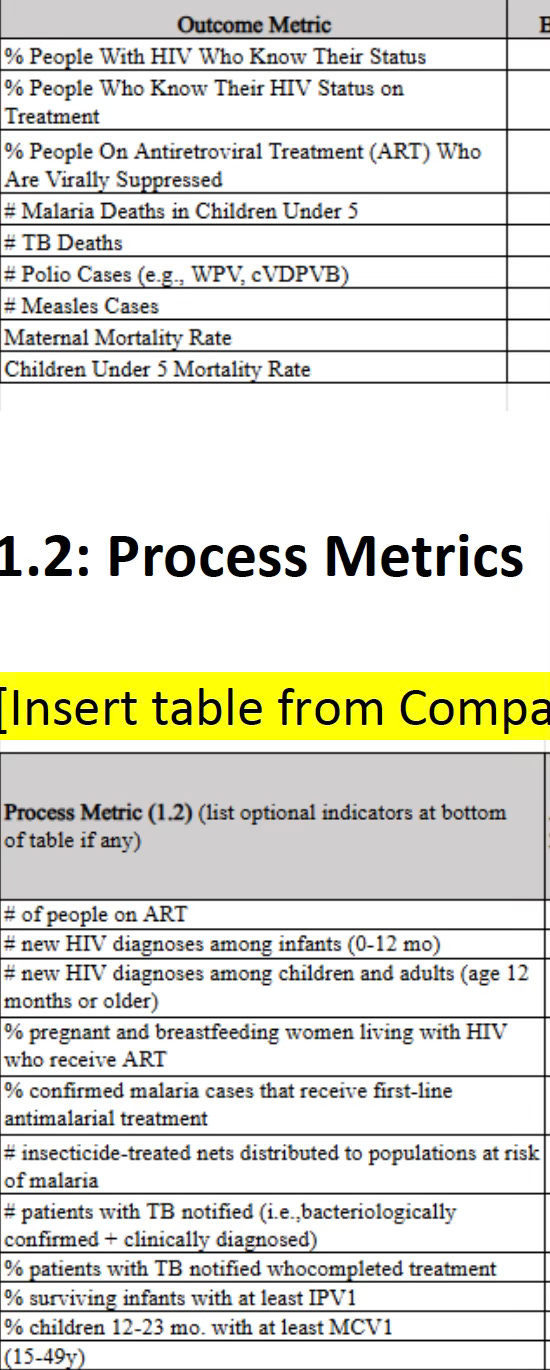

As I covered in posts in 2025, the outcome and process metrics for each health area are, variously, simple, vague and difficult to measure to such an extent that one might argue the folks who selected them do not have a genuine, overriding interest in tracking the health impact of the AFGS investments.5 The instructions appear to have been written by the same folks. A country could submit two pages on the seven total process and outcome metrics in the HIV health area, with a total of three to five strategies for all seven metrics—and meet US government expectations.

Alt text: A screenshot from the pdf of the Implementation Agreement that mainly recaps the metrics used in the Memorandum of Understanding template that went to countries in October 2024—except when it doesnt, which is in the age bands. This table lists 0-12 and 12 months and up. The MoU Template listed 0-18 months and 18 months and up. Is this a decoy document or do the folks building the forms just not care? I almost hope it is the latter. Prove me wrong.

It’s okay dude. I’m not mad at you.

Because if a two page memo is acceptable, so is a highly-specific plan detailing granular epidemiological data, strategic key activities and ambitious timelines. Evidence on disproportionate rates of new HIV infections (and undiagnosed, existing infections) in adolescent girls and young women or any other age band eliminated in this template could be introduced and used to substantiate strategies that support young people’s linkage to testing, treatment and prevention. The US is signaling here that it doesn’t want to supplant national processes with its own long strategies tied to bilateral funding. Fair play to that. The document should be short, provided it makes liberal, pointed use of references to extant strategies and data sets. An AI-generated redux of the national HIV strategy won’t cut it. A brief narrative with lots of references by page, section and line number to the sources that describing specific workforce, location, service packages and so on could work. The explicit direction to consider resources from the Global Fund—which are excluded from domestic resource calculations—even invites countries to plan somewhat holistically, capturing what an overall program strategy might look like, inclusive of elements not covered by the AFGS funds.

For those who want to understand how different these directions are from every prior US health investment that sustained major Congressional support and delivered impact for decades, and who get to the parenthetical in the footnotes that it broke me open a little bit to write, here’s some context.

Every health area covered by the MoU has, for years, been the subject of massive standalone documents created both by the US government and by the countries in every nation where MoUs are being signed that included detailed annual and multi-year strategies.

Every one of these detailed annual and multi-year plans has many (like more than 3 to 5) strategies for achieving impact for each individual metrics in the MoU. As just one example, consider the process metric that is written, in the Implementation Planning tools, as “# of new diagnoses among children and adults (12 months and older).” All of the available evidence about HIV testing and, for that matter, most of public health programming, says you need to segment the populations who will be using your services, work with them, understand them and co-design public health programs accordingly. Adolescent girls and young women who are in school need something different from adolescent girls and young women who are out of school. Older men need something different from toddlers. Each “something different” is a strategy: where the testing is offered, who is offering it, how late it is open, what else is offered by the testers, and so on. It isn’t possible to do an implementation strategy for one of the seven HIV metrics with three to five strategies unless each strategy is so broad that it isn’t a strategy at all, but something aspirational that would still need an implementation plan prior to execution.6

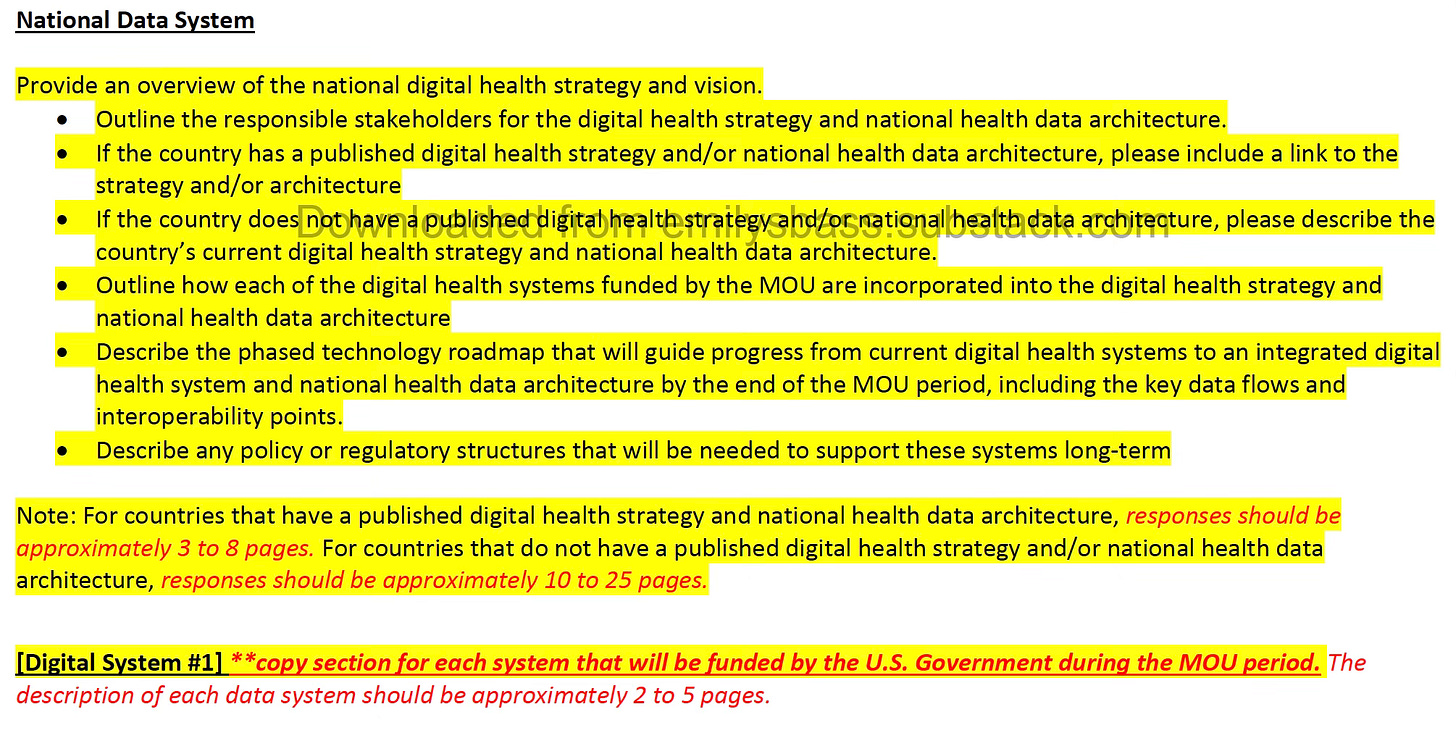

It’s important to note that while the Implementation Plan template suggests that the US authors are not looking for an actual, impact-oriented implementation plan on health impact,7 there are other sections in which the U.S. is very clear that it wants extensive information, including references to existing strategies. One example of this for the country’s digital health systems. As shown in the screenshot below, the Implementation Plan template asks countries to supply a link to their National Digital Health Strategies and, if they do not have one, to essentially write one as part of the implementation planning process. National digital health strategies cover far more than the IT infrastructure, interoperability, server hosting and other capabilities relevant to the data systems that the U.S. has secured log-in credentials for via the Data Sharing Agreements annexed to the MoUs. These strategies cover ethics, governance, telemedicine, data gaps, data equity, birth and death registries and whole lot of other information. They are long, ambitious, complex and—in many countries signing these agreements—grievously underfunded. Asking for the strategy affirms U.S. interest in the countries data. Not asking for the comparable health area strategies suggest…something else.

Alt text: A screenshot of a pdf I made of a version of the Implementation Agreement template. The fourth bullet reads, “outline how each of the digital health systems funded by the MOU are incorporated into the digital health strategy and architecture.” Given that these agreements are, in some instances, introducing new private sector partners and/or expanding the role for pre-existing US-owned companies working in country, and that these agreements were signed in the last 30 days, and that most national strategies are updated every five years, this request feels just a little bit rich. Whoops. I mean a little bit of a reach. I think.

The Implementation Agreement direction on pre-requisites for the purchase of non-US manufactured commodities

For many low and middle income countries, pooled procurement,8 and local and regional manufacturing are widely understood to be remedies for the stark global inequity in access public health goods—from vaccines and tests for SARS CoV-2 and mpox, to GLP-1 inhibitors, lenacapavir for HIV prevention, and so many other lifesaving commodities. For example, the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention African Pooled Procurement Mechanism seeks both to consolidate purchasing efforts across the continent and to support the African Union’s goal of meet 60 percent of the continent’s vaccine needs by 2040.9

Against this backdrop—and the US government’s public avowal that supporting national country ownership of health systems and plans is a core component of its current strategy—the fine print on what commodities can be purchased with US dollars and by whom is very important.

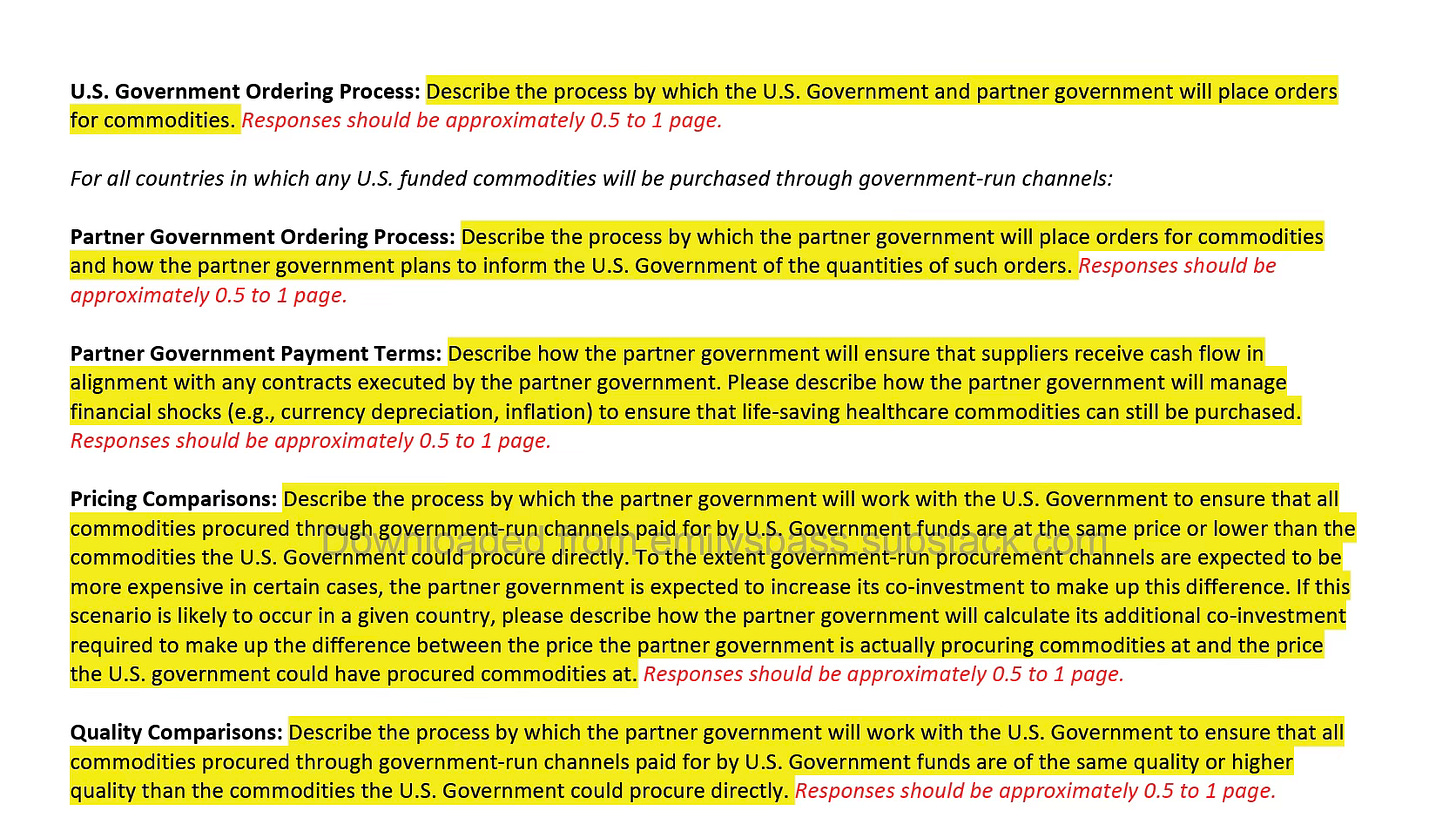

The orange-highlighted text and the screen shot below show the information countries must provide in order to purchase themselves, for example through pooled procurement mechanisms.

Pricing Comparisons: Describe the process by which the partner government will work with the U.S. Government to ensure that all commodities procured through government-run channels paid for by U.S. Government funds are at the same price or lower than the commodities the U.S. Government could procure directly. To the extent government-run procurement channels are expected to be more expensive in certain cases, the partner government is expected to increase its co-investment to make up this difference. If this scenario is likely to occur in a given country, please describe how the partner government will calculate its additional co-investment required to make up the difference between the price the partner government is actually procuring commodities at and the price the U.S. government could have procured commodities at. Responses should be approximately 0.5 to 1 page.

Quality Comparisons: Describe the process by which the partner government will work with the U.S. Government to ensure that all commodities procured through government-run channels paid for by U.S. Government funds are of the same quality or higher quality than the commodities the U.S. Government could procure directly. Responses should be approximately 0.5 to 1 page.

Alt text: Another screenshot of another page of the Implementation Agreement I reviewed and reformatted. Please don’t ask me why I retyped some of these screenshots and not others. Or: please become a paid subscriber to support equitable Stack access—and then ask.

There’s a lot happening in that section on commodities, and for some reason I keep thinking I hear someone whispering “Emily, your response should be approximately 0.5 to 1 page”—so I’ll be brief at the top and you can move onto the next section, if you want.

It’s utterly reasonable, defensible and precedented to require that money for medical commodities is used to purchase the highest-quality products at the lowest possible price. It’s utterly reasonable, defensible and precedented to require quality assurance. These requirements are also pretty feasible for low-income countries to meet in a world where the US is a member of and/or collaborates with the World Health Organization, Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other regional and multilateral entities. But these agreements aren’t being signed in that world. Depending on the extent to which America’s broader foreign policy agenda is implemented through the AFGS, there could be added costs, complications and tradeoffs for countries that want to work with America and the rest of the world.

America First, indeed.

For many countries, the answer to the quality comparison question will be something like “We will only purchase WHO pre-qualified commodities.” The WHO uses its pre-qualification function to designate commodities as meeting its standards of quality, safety and efficacy. Many low-income countries rely on WHO “pre-qual” to select who they purchase from because they have gaps in their own regulatory capacity. Under the Trump Administration, the United States of America exited the World Health Organization. If WHO pre-qual is not accepted as an answer to this question, and there is no acceptable regional alternative, then countries could be unduly constrained in their purchasing options.

The America First Global Health Strategy endorses pooled procurement mechanisms. It also says that “The U.S. government will establish or contribute towards one or more pooled procurement mechanisms for purchasing these commodities.”10 What’s this about establishing pooled procurement? In fact, the US government has had—and maintains—a giant supply chain management contract, previously run by USAID and now housed within the State Department that harnesses the full purchasing power of the US to negotiate prices on commodities. This text paired with the Implementation Template text suggests that the US could opt for using its own procurement mechanism for some or all of the program, instead of contributing to ones run by the APPM, UNICEF, and other regional and global entities.

The text also makes it clear that going with locally manufactured and procured products that are in any way more expensive than US-procured commodities will cost countries more. However new procurement processes and regional manufacturing capacities have up-front costs that could impact prices in the short-term. An implementation approach cognizant of these realities might put in transition benchmarks or criteria by which a higher cost would be tolerated for a specified period of time or under specific conditions, such as in support of local or regional procurement, provided that over the course of the agreement period, the difference zero’ed out.

The Implementation Process Overview + available MoUs + Implementation Agreement Template on which entities are likely to receive funds on April 1 2026

One frequently asked question among the MoU watchers I know is: who’s actually going to get the money on April 1 2026? Is it going to be governments receiving “on-budget” support—funds that flow through national financial management systems? Is it going to be implementing partners that still have contracts with the US government? Or a combination of both?

The answer was implied in the MoUs. Uganda’s states that the US will “incrementally” transition to on-budget support, with no timeline or quantification of the increments. Kenya’s stipulates that the government will review all of the contracts with implementing partners providing services. No agreement has firm timelines for moving to government to government support, even though the press releases from the Department of State seem to suggest that this shift is imminent.

Instead, the Implementation Process Overview further reinforces the impression that much of the money flowing on April 1 will go to implementing partners. It is a five step document, of which Step 1 is: “Review Existing Implementing Partner Awards.”11 In this step, existing IP awards are assessed with determinations about continuing, cancelling or modifying based on, among other things, performance against targets. This is a strange and wondrous thing to see appear again, as the exact same effort was tasked during the foreign assistance review back in 2025. This is a walk back through that changed award landscape, I guess.

Step 5 is “Create New Awards Including Government-to-Government Agreements.” This last and final step notes that (a) guidance for government to government agreements will be forthcoming in late January and (b) that, “Based on U.S. law, the first step in each government-to-government agreement process will be to conduct a risk assessment that will ensure the structure of the agreement and the proposed amount of government-to-government financing is commensurate with the underlying risk context.”

Let’s be clear. There is no doubt that the US government has designed these five-year agreements to handover health investments to the national governments. There is nothing wrong with money continuing to flow through implementing partners that are meeting targets and delivering quality services. The Process Overview reflects a clear and realistic articulation of the time it takes to do things with foreign countries in accordance with US law, the implied intention of the Department of State to operate in accordance with that law, and the logical conclusion that an investment aimed at maintaining continuity of services in the next year will, in many instances, be an investment in implementing partners, not direct government-to-government on-budget support.

In other words, this process is not going to cause ongoing implementing partner activity providing quality care to halt abruptly, with little warning and no period of transition for handing over to the host country government. It is not going to violate US law. It is going to prioritize continuity, joint planning and a transition period.

I started crying a little as I wrote that description of a measured, sensible approach to financial transitions. It stands in stark contrast to the events of 2025 that started almost exactly a year ago. But don’t worry. It’s okay dude. I’m not mad at you.

Well, I think I see Starlink in the US Department of State press release on the Botswana agreement, which states, “The MOU will modernize electronic medical records and disease surveillance systems, including U.S. supported networking infrastructure that may leverage American satellite-based technologies to strengthen outbreak preparedness while advancing U.S. technological leadership.” https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/12/advancing-the-america-first-global-health-strategy-through-landmark-bilateral-global-health-mous. Starlink, Elon Musk’s space-based satellite empire, rocked up into Botswana as an internet provider in 2024 after a bit of a struggle (https://techpoint.africa/news/starlink-launches-in-botswana/), and everyone I’ve chatted with thinks that’s the company in question in this presser. Ever since Rwanda’s press release, named the private sector companies getting US government and government money (Gingko and Zipline) triggered a flurry of interest in the private sector beneficiaries, the Department of State has gotten a little coy about naming the American companies are benefitting from these agreements. But in the case of the DoS press release on Botswana, IYKYK. While we’re here, and because it’s been a while, I’ll point out that the Botswana Embassy press release—which would have been scrupulously reviewed by the folks in Foggy Bottom—had no such wink-wink language. https://bw.usembassy.gov/united-states-signs-487-million-mou-on-global-health-with-botswana/ Maybe because a payout for the ex-DOGE head plays better in the US than Botswana, and the local media listen to the Embassy Public Affairs office? Who knows.

I’ve sourced links to a lot of these press release. One is in the footnote above. Others are in previous stacks. You can go look for yourself, or trust me on this: There is not a single numerical measure of health impact in any of the US government communiques about these Memoranda of Understanding. Not one quantification of HIV infections averted, not one number of polio immunizations provided. No integers at all except for the date, dollar amounts committed by the US and the co-signatory, and the total number of agreements the US is planning to sign.

Grammar is the guest star for this Stack’s footnotes. In the sentence this note is sitting in, I’m using passive voice, which I detest even as it creeps, daily, into my writing like some kind of weird mold. In this case, I’m using it intentionally because: who the <*&^@ knows who is sending these messages into the ecosystem of people who literally or figuratively can’t quit the Bureau of Global Security and Diplomacy. I have no idea. I just know one day everyone was telling me that the Implementation Plan phase was going to solve everything. It was creepy. Like that mold.

I am beginning to hear noises that Bridge Plan funding payments have been delayed, and that moving new money based on these MoUs could also be delayed.

New year, old topic. I have not forgotten that the US Department of State Bureau of Global Health Security and Diplomacy has not released any of the Monitoring Evaluation and Reporting indicator data for FY2025 even though that data was collected and exists. I started the Stack with a post on the data blackout. If I don’t mention it all the time, trust me. I think about it every day. And I’m not alone.

In the interests of brevity, I’m retreating to the footnotes to describe the nails-on-a-chalkboard aversion I have to the grammar of the last sentence in the pricing comparisons section, which ends with the word “at” when it could have been avoided, as in “the price at which the US government could have procured commodities.” Footnote readers (ie people who like wormholes and diversions) will not be surprised to hear that I embarked on a pique-fueled internet search about the grammatical acceptability of ending sentences with prepositions. But I hope some of you will share my utter surprise that (1) it is allowable (it shouldn’t be) and (2) the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says so on a live page that (a) does not have the Trump Administration's content disclaimers on it and (b) references the 2020 comedy “The Last Human on Earth,” calling it “eerily prophetic.” Really. I am not making this up. The CDC can say we can end sentences with prepositions even though it can’t say that childhood vaccines are safe, effective and essential public health tools. It can reference a television show about a deadly virus sweeping the planet even though it is no longer allowed to perform almost any of the functions that would prevent such a scenario from happening again. This could never have fit in the text, but it’s great for a footnote. Which is where you’re at.

To the extent that the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief was defined by its detailed, evidence-driven, lengthy, measurable country operational plans, developed with robust input from impacted communities alongside government, these implementation documents make it entirely clear that PEPFAR no longer exists. We can talk about whether the Argo was the same ship or not after all of its wood was replaced. I’d rather talk about Mrs Ramsay dying in the parentheses. PEPFAR is a program with distinct attributes, approaches, ethics and processes, led by a whole-of-government process in which every agency is functional, funded and tasked to do what it can do best to ensure that lives are saved and HIV infections averted. (PEPFAR is gone.)

Pooled procurement refers to the process whereby purchasers, such as countries, aggregate orders for a specific commodity, thereby leveraging collective bargaining power and attracting suppliers interested in competing, with lower prices, for a larger and more lucrative order than any single country could place on its own.

https://africacdc.org/appm/

https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/America-First-Global-Health-Strategy-Report.pdf

I am not, for now, reproducing this document — I didn’t forget or get stingy but I can’t right now.

Interesting. You set up as opposition and critic but in reality you are both insiders with privileged access to government docs before the actual frontline workers or people living with HIV who are downstream in your discussions.

I get you are angry about USAID and other partners and perhaps your HIV agendas being threatened and the “trauma” but you should state your COIs so readers can understand your framing.

Funny how both the activist critics and government insiders have a hard time acknowledging that that the system was severely broken. The simplest of AI and PubMed assisted search on HIV, PEPFAR, UNAIDS and epidemic shows that the US and Global Fund has spent over $100Bn in Africa alone (or more?) yet about 11M (~25%) of people living with HIV are still not accessing successful treatment.

Meanwhile, US literally has hundreds or even thousands (?) of paid partners, with some CEOs making nearly 2M a year. What was everyone doing with the cash that was meant for the poorest people to get treatment and care as part of prevention along with other interventions?

Unfortunately, your dialogue or back and forth with the US government guy, your friend, is abstract with lots of jargon as if neither of you are stating or willing to share the stark reality. AIDS conferences with 10,000 attendees each year at what cost? and what benefit? Faux community organizations with only leadership and no real constituencies to speak of, thousands of research articles every year, etc. AIDS speak about stakeholders and community engagement and trauma but where is the concern about waste and the resulting treatment gap for people living with HIV—mothers, children and fathers, families, communities? Where is your outrage over the 500,000 children in Africa who are not on successful treatment? It is a 100% fatal virus without treatment.

Is everyone OK with CEOs of AIDS Inc getting near 2M per year? And should each country have 4 or more US agencies and 40-50 or more partners at enormous costs? Does USAID and CDC and DoD and NIH and Peace Corps really need to have their hands on the wheel in every country? And if they spent their time fighting and at odds over strategy then at what cost? How many contracts did USAID manage? CDC? How many HIV staff and jeeps and health care workers did US employ by country? What did they actually do with the money?

Let’s get concrete please. Emily you have the inside track so you should be able to find out. Too much inefficiency and entitlement—time for both of you to come clean and put forward facts and priorities. What do you propose? For example, what level access to care and treatment for people living with HIV—is it ok that 25% are left in the cold? or 14% or?? How many US partners and US supported staff? how many US agencies n country? Number and type of US supported stand alone programmes and proposed impact on epidemic, giving direct budget support to countries, or? etc.

Emily you seem to have the docs before everyone else so you might want to think about the above and get some help understanding how to end the epidemic (e.g., locally produced drugs at twice the cost and half the quality is not going to be helpful). Or perhaps you can use your pre-blogger experience (remind us again about your work in country please) and explain it for the readers—please be concrete about your priorities and framing. Tell us concretely how you would manage this sort of change to improve efficiency in a short time frame? Micro level detail vs broad planning brush strokes? It appears to be a major shift and experiment—shame it did not happen under more controlled orderly circumstances but everyone was probably too busy spending like drunken sailors to notice the need for reform and the huge gaps that were not being addressed with the billions in investments.

One last thing—why is the government leaking to you Emily and not the governments it is working with? When do they get the documents? After everyone else has a chance to study them and prepare for negotiations? That says it all about AIDS Inc. Inside baseball neocolonial model that needs to change. Perhaps that is what we are looking at—painful but needed change.